06 Oct Tate Springs: Tennessee’s Lost Mineral Water Resort and Golf Haven

Long before modern spas and wellness retreats, people traveled far and wide to “take the waters” — seeking the healing powers of natural mineral springs. In East Tennessee, one of the most celebrated of these destinations was Tate Springs, a luxurious pre–Civil War resort in Bean Station, where health, high society, and hospitality once met amid the rolling Appalachian foothills.

The Birth of Tate Springs Resort

In 1865, Samuel L. Tate acquired roughly 2,500 acres of land in Bean Station, Tennessee. The property, rich with mineral springs, already featured an old hotel just north of where Tate would later construct the grand Tate Springs Hotel. Within a few hundred feet of one of the springs, the new hotel became the centerpiece of a resort that would soon attract visitors from across the country.

About 11 years later, Thomas Tomlinson, a veteran who had fought for the Union Army during the Battle of Bean Station, purchased the property. His family saw greater potential in the waters themselves. By the early 1880s, Tomlinson’s daughter, Anna Martha Ragsdale, and her husband began to advertise and bottle the spring water, convinced of its curative powers.

Epsom Water: A Miracle in a Bottle

The mineral water at Tate Springs was rich in magnesium and iron, and quickly gained fame as “Epsom water.” Believed to alleviate kidney, liver, and stomach ailments, the water was bottled and shipped worldwide, sold in drugstores for 10 cents a drink. At the height of its popularity, the resort shipped 400 gallons daily.

The Tate Springs mineral water joined a larger regional trend. From Montvale Springs to Oliver Springs and Whittle Springs, East Tennessee became a hotbed for hydrotherapy tourism in the 19th century. The arrival of the railroad made travel easier, and entire communities grew around these wellness destinations — a blend of scenic beauty, health-seeking, and social prestige.

A Playground for the Elite

As the reputation of Tate Springs grew, so did its clientele. The guest registry read like a who’s who of American industry and politics:

- The Rockefeller family

- The Firestones of Ohio

- The Vanderbilts

- Senator Oscar Underwood, once a presidential candidate

- The Mellon family

- And Henry Ford, who famously met John Jarnagin during his stay — an encounter that led to the founding of Jarnagin Motors in Grainger County in 1916.

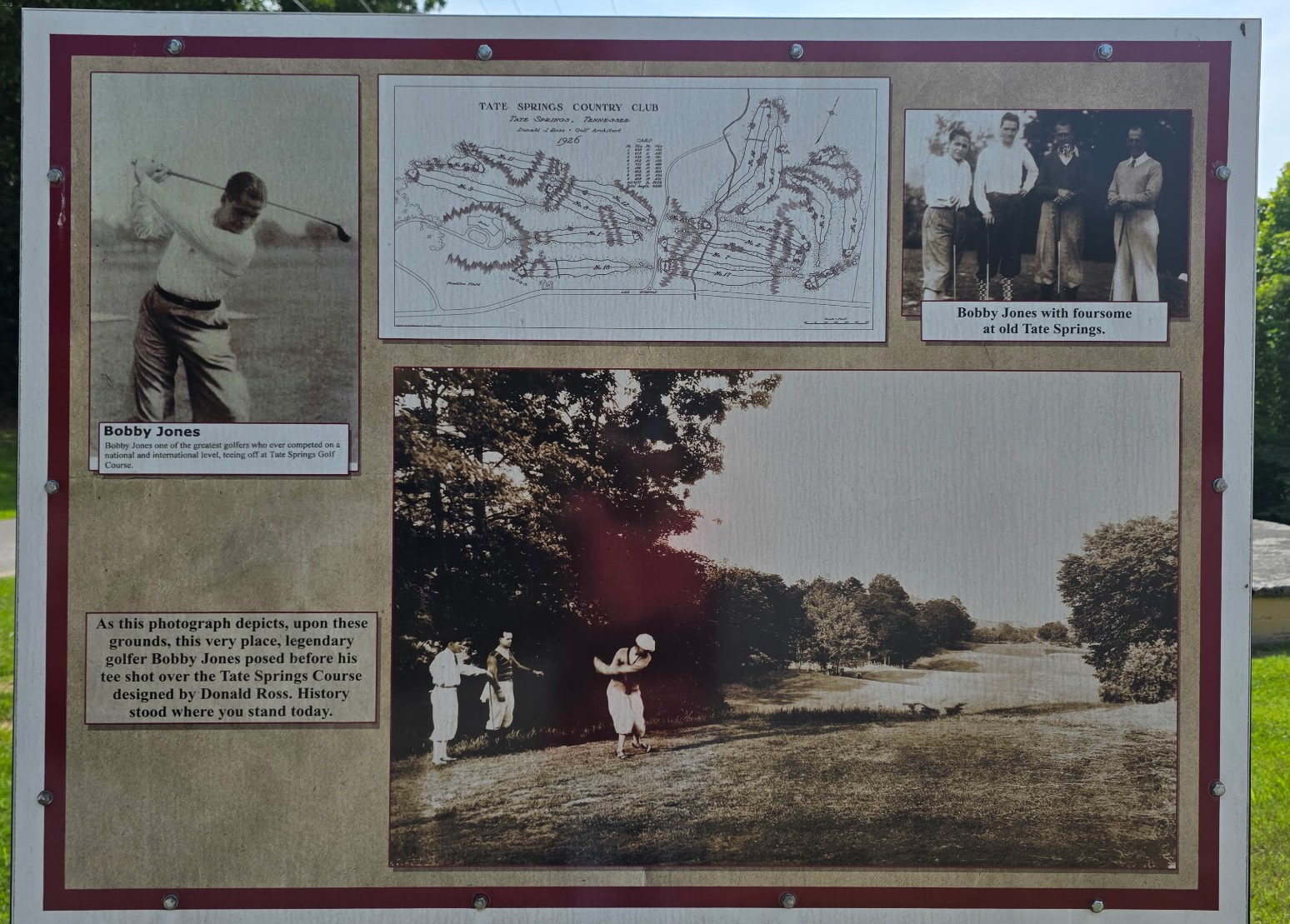

Visitors came not only for the healing waters, but also for the resort’s world-class amenities, including a renowned golf course — one of the finest in the South at the time. The course, set against sweeping mountain views, was both a social hub and a sporting challenge, drawing guests to leisurely rounds under the Tennessee sun.

Decline and the Waters’ End

The golden era of Tate Springs came to a tragic end with the rise of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and the construction of Cherokee Dam. On July 1, 1940, the day before construction began, the resort still welcomed guests — but by the following years, its fate was sealed.

The creation of Cherokee Lake submerged the golf course and relocated the highway, cutting off easy access. The hotel’s water and sewage systems were destroyed, and by 1941, the once-famous Tate Springs Hotel closed its doors.

The property was later purchased for the Kingswood Children’s Home, and children lived in the old hotel until it burned down in February 1963. Thankfully, no one was injured. Today, only remnants remain — a concrete-covered basement and the dumbwaiter shaft that once carried meals up to the grand dining room. Yet these silent relics speak volumes about a forgotten era of Southern elegance and mineral water magic.

A Legacy Beneath the Lake

Though the spring waters no longer flow freely and the fairways lie beneath Cherokee Lake, the legacy of Tate Springs endures — a reminder of a time when people believed in the earth’s healing powers, and when a small corner of East Tennessee was a world-renowned destination for wellness, recreation, and high society.